By François Henri Guyon

Originally published in Punta Dritta July AS XL (2005)

Sword

For much of the middle ages it was uncommon for people to wear swords as part of everyday dress. A knight would wear his sword on ceremonial occasions, and travellers would wear swords on journeys, but most people in England and France would carry only their belt knife.

In the early part of the Renaissance period, it became common for a gentleman to wear his sword at all times and in all places. Generally, this coincided with the decline of the land-owning class and the dramatic impact of plague on the population.

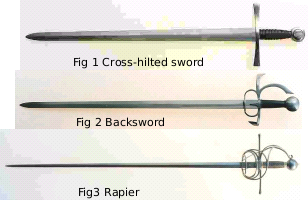

Initially, the sword was the same as used on the battlefield: broad bladed and cross hilted (Fig 1). Such a sword could hang from a person’s belt with little problem.

As time progressed, however, the hilt of the sword became more complex to protect the hand and the blade became longer in an attempt to outreach the opponent. Some rapier blades reached between 48 and 60 inches in the length, making the simple act of drawing the sword difficult and dangerous.

George Silver, a conservative anti-rapier voice of the late 16th Century, writes that the normal length of a blade should be between a yard and one inch for the shortest man, to a yard and four or five inches for the tallest. We can assume, therefore, that rapiers commonly being used in London at the end of the century were longer than this.

In order to wear such a long rapier, it becomes necessary to angle the blade hanging from the belt, to prevent it dragging along the ground. There were three common devices used to accomplish this: Slings, Hanger and Baldric.

Belt and slings

The Belt and Slings (Figure 4) is a simple affair. Two or three slides grip the scabbard of the sword. A strap (called a sidepiece) connects from the slings to the belt on the opposite side of the body, and is adjustable to control the angle of the sword.

Whilst this will keep the sword from the ground, the narrow range of the attachments will allow the sword to flap around a bit. It is not unknown for the slings to have a second strap around the leg to give more stability.

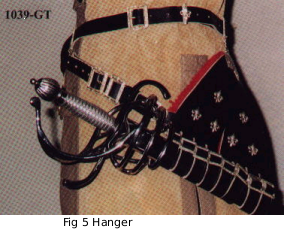

Hanger

An adaptation of the Belt and Slings is the Hanger (Figure 5). This increases the number of slides and supports them with a broad panel of leather. This tends to be much more controllable and stable.

Both the Hanger and the Belt and Slings can be attached to a girdle or normal belt through the use of frogs, or friction loops, on the belt.

Baldric

The final way of carrying a sword is the baldric (Figure 6). This is a simple belt, worn over the shoulder and sloping down to the opposite hip. The sword is attached by use of slides. There is, however, no easy way to wear a dagger on the baldric and so it is often seen as a military fashion or a very late period fashion.

Bowing

All these ways of carrying a sword require the rapier to trail a long way behind the body. When bowing from the waist, this causes the end of the sword to tip up (usually into somebody else). This could be a cause of a duel, so great care was taken to control thei sword when moving around. However, it is quite threatening to grip the rapier constantly by the handle, and this could also get the wearer into trouble.

For a right-handed fencer, the key is to use the inside and outside of the left hand to guide the rapier in the movement. Bowing is altered to the form of Reverenza used in Renaissance dance. The drawing back of the left foot allows the wearer to push the hilt wide of the body at the same time as extending the arms in the bow. This movement pushes the tip of the sword close behind the left ankle and thus out of the way.

Cape

The fashionable style for a cape was to wear it over the left shoulder. This leaves the sword arm free, whilst still affording some warmth and allowing the embroidery to be displayed.

If the cape was fastened with ties or buttons, they would run to the right armpit, tying diagonally across the chest. This leaves the left arm free to grasp the knife, affixed to the back of the belt, whilst the right arm is able to reach overhand. An Alta guard is almost impossible to achieve if the cape is tied over the right shoulder.

Hat

Surprisingly enough, most people in medieval and Renaissance Europe wore hats. I say surprisingly, because it is uncommon to see people in the SCA wearing them.

A fashionable Renaissance gentleman would feel just as undressed going out without a hat, as without his sword. Given the cold snap that covered Europe during the 16th century (which froze over the River Thames at times), it was very rare to see somebody without a hat.

During the bow, the hat is tipped or removed entirely, depending on the rank of the person you are being presented to: a touch of the brim or tug on the flat cap for a common acquaintance; complete removal for a lady or ranked person.

This is difficult to coordinate with sword and cape, especially on the dance floor, without disembowelling somebody behind you. A soft cap is gripped by the brim and replaced from the back of the head forward. This allows the drape of a soft cap to catch the back of the head. A solid hat is opposite, where the hat is gripped by the front of the brim and replaced on the temple and slid back into place.

Images taken from www.armor.com and www.imperialweapons.com